We once had a conversation with our colleagues that drifted into the decolonization movement and how we as Africans are perceived; our style of dressing, how we wear our hair, and how our languages are influenced by colonialism and more recently, pop culture trends. While referring to one of our female colleagues who was wearing an African print shirt and has short, close-cropped natural hair, there was a shared perspective within the group that more “enlightened Pan-Africans” tend to wear “traditional” African print clothes and natural hair as a resistance to Western styles that have come to represent a stereotypical version of professionalism.

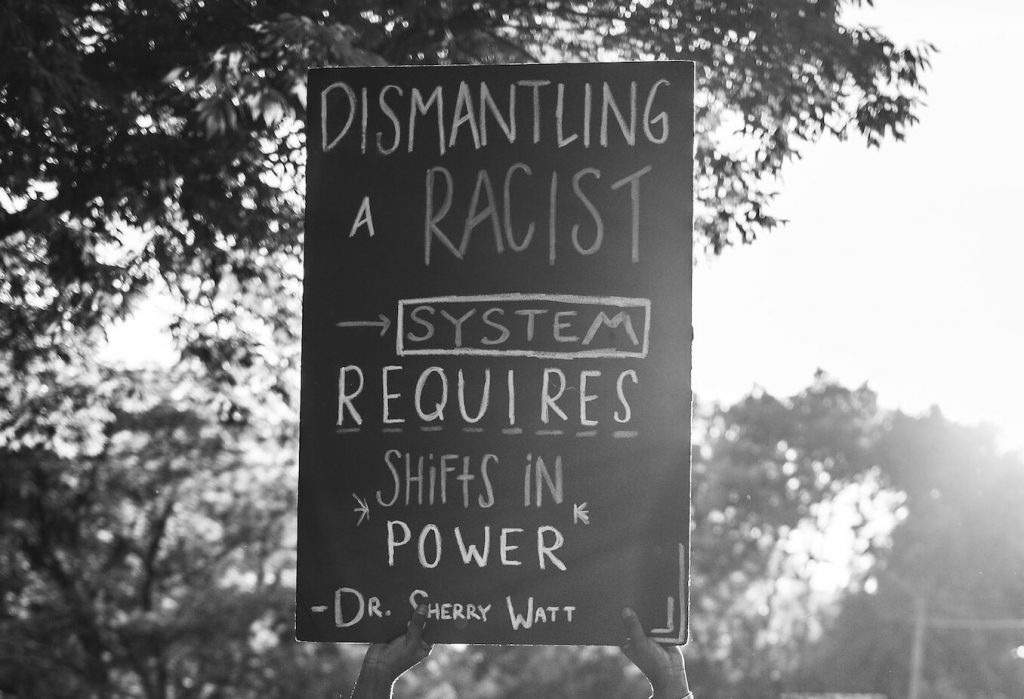

During the 1960s and 1970s, Black nationalists began renaming themselves to shed off slave owners’ names as a step towards self-definition and liberation. Therefore, while it was easy to understand our colleagues’ acknowledgement of the dress and hairstyles as somewhat inherently revolutionary, we were uneasy about how much value we seem to attach to what we colloquially refer to as the ‘aesthetics’ of decolonization. Accurately assessing Africa’s past and present is essential to undoing the effects of colonization, shifting power and reimagining a future in which aid is done differently.

We were uneasy about how much value we seem to attach to what we have come to colloquially refer to as the ‘aesthetics’ of decolonization.

In 2022, CivSource Africa set out to do just this. As a Pan African feminist philanthropy support organization and grant maker in the Global South, we have the privilege of sitting between funders and civil society organizations. We curated a series of six conversations with local Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and International Non-Governmental Organisations (INGOs) working in Uganda to introspect and participate in truth-sharing exercises. These conversations provided a space to acknowledge the structural inequities, racism and biases that exist within the international development aid sector and, subsequently, to reimagine what the sector could look like for organizations and communities in the Global South through a decolonial lens.

The decolonial approach was a relevant inroad into the #ShiftThePower conversation in Uganda. So much about development work has colonial undertones. First, we had to uncover and acknowledge the factors that have led us to this point; the most conspicuous being power. Power and privilege, as Kathleen P. Enright posits, are inherent to philanthropy – our history and resources make it unavoidable. Shifting the power calls for more power consciousness and an honest evaluation of our relative positions and the inadequacies or advantages inherent in these positions. As the conveners, we also held various identities; that of a Pan-African feminist funder (through our funding arm, CivFund), a philanthropy advisor and an implementer.

In some of the conversations we convened, we were a funder, in others a local non-profit or both. Innately, in the rooms in which we were more renowned or perceived as a funder, the direction of the conversations had the undertones of risk aversion; more appreciation, the absence of critique perhaps from the fear of biting the proverbial hand that feeds one.

This meant that our own power consciousness was heightened because of the various positions and identities we hold, and our inherent power inadequacies and advantages. In some of the conversations we convened, we were a funder, in others a local non-profit, and sometimes both. Whenever we were perceived more as a funder, the conversations had undertones of risk aversion; more appreciation, the absence of critique perhaps from fear of biting the proverbial hand that feeds.

The critique was more pronounced and directed to all funders “except us” with participants treading carefully when it came to us as the convener. In spaces where we were perceived as both funder and implementer, trust issues seemed to arise, and with that, a bit of pressure on our part to opt for an identity that eased and supported experience-sharing and truth-telling.

This experience has challenged us to acknowledge trust as an infinite resource, and the need to extend “our horizon beyond money as the central driver of change, and to place greater value on other kinds of infinite non-financial assets and relational resources (knowledge, trust, networks).” Trust is the currency that enables power to shift and to erode the self-censorship we had sensed. Trust was the language that needed to be spoken to enable new ways of being and doing, rather than to constrain them. It’s the foundation for the global solidarity needed for us to both embrace and actualize a “good society.”

After a year of uncomfortable discussions on the topic of decolonizing aid, we find ourselves at a crossroads. One path leads to more questions, another laden with a realization that has hit a little too close to home.

The nuances that enable the system, we have come to feel, are in the people: people like us and people like you.

On the one hand, we seem to have arrived at more questions than answers about what a true shift in resources, mindsets, attitudes, and therefore, what power looks like. We have grappled with whether a shift in resources alone is, in fact, a solution to skewed power relations between the Global South and the Global North. Similarly, could a shift in power simply move the center from one entity to another without interrogating or even seeking to dismantle the structures of oppression upon which that power is exercised?

While our quest continues, certain realizations have become evident to us. There appears to be an almost subconscious inclination to maintain the structural oppression upon which power has been exercised for so long. Yes, there are systems which have propelled power imbalances, and embracing a “good society” could be one way out of this mire we find ourselves in. But we have come to feel that the nuances that enable the systemare in the people – people like us and people like you.

As we undertook this work, we came to appreciate the depth of our personal conditioning as well as that of the staff, leadership, and organisations that engaged in these conversations. We became more aware of the extent to which our own personal perspectives and those of others involved in the discussions have been shaped by existing norms and practices of aid. The deeply ingrained ways in which development and aid is approached has created a level of rigidity and discomfort that stifled the creativity and radical courage required when contemplating alternative approaches. We have been robbed of our imagination to imagine alternative ways of doing. Amidst these realizations, how do we ensure that the movement is cognizant of these nuances? In our work to shift power and decolonize aid we might inherit the system instead of dismantling it. If we overlook these nuances, do we not run the risk of potentially perpetuating them in the new abode of the shifted power? Without power consciousness and an awareness of individual biases, we stand to change the location and aesthetics of the systems but not the systems per se.

Olum Lornah Afoyomungu is a Program Associate at CivSource Africa and Ainembabazi Madonna Vicky is a Philanthropy Program Lead at CivSource Africa.

If you liked this, you might also like:

Localization, decolonizing and #ShiftThePower; are we saying the same thing?