This piece is part of a series of articles exploring the topic of civil society resourcing, and why this needs to be rethought – particularly in terms of placing more value on civil society’s “intangible” assets. See other posts: Rethinking civil society resourcing and Can money buy everything? Resourcing in the new system.

If we want to shift from the “system we have”, to “the system we want”, what needs to change? What will the new system look like? What will it take to move from where we are to where we want to be?

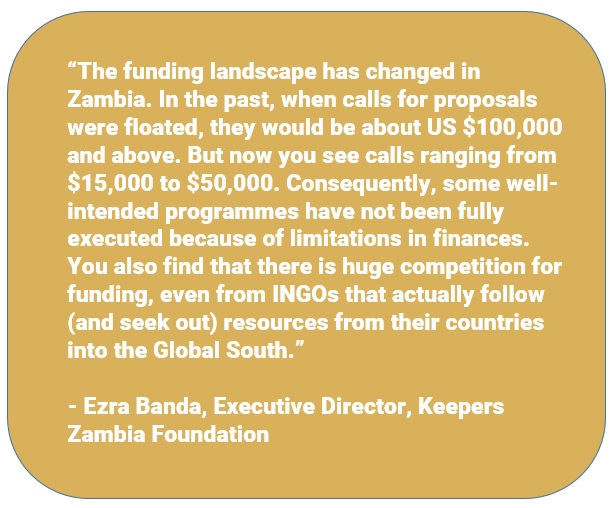

These are some of the questions that a team of Zambian civil society organizations has been grappling with over the last four months. In 2011, Zambia was re-classified as a middle-income country. One of the immediate impacts of this reclassification was that international donors started to withdraw their support, leaving behind a big funding gap in the country’s civil society sector. Anxiety over funding, accompanied by a deep sense of vulnerability, has forced civil society organizations in Zambia to consider alternative ways to fund their work.

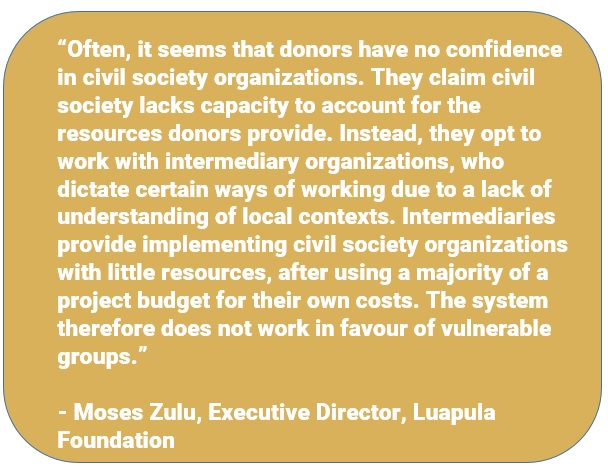

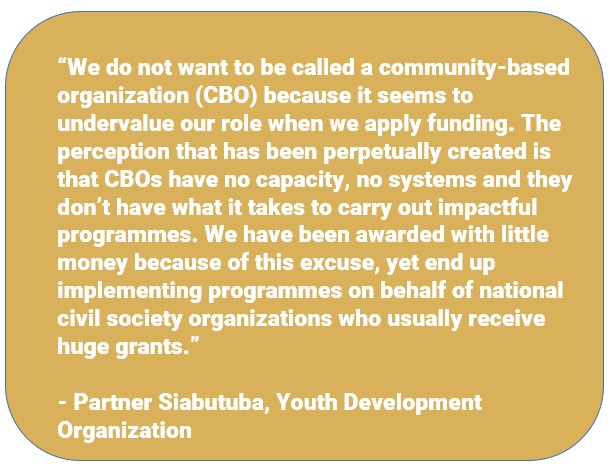

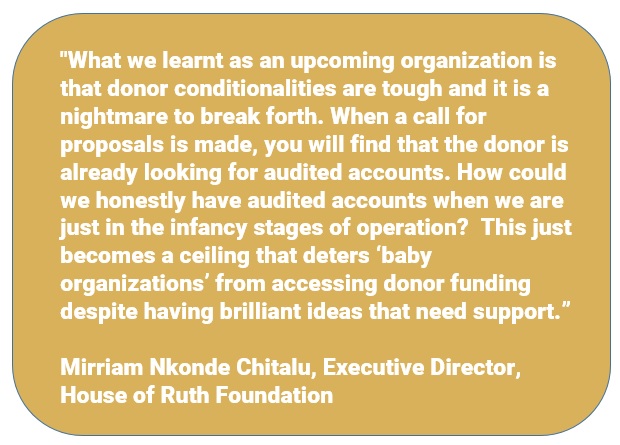

Over the course of February 2022, the Zambian Governance Foundation (ZGF) hosted a series of conversations with local civil society leaders, aimed at examining the current situation facing NGOs in Zambia and at exploring alternatives. Both national and community-based organizations participated in the discussions, which exposed the extent to which organizations are trapped in endless project cycles and an ongoing dependence on foreign funding. “Most organizations have focused on writing project proposals in order to secure funds to continue operating and surviving. This, however, undermines the financial sustainability of civil society organizations and creates a culture of ‘chasing money’, rather than supporting communities,” lamented the director of one organization.

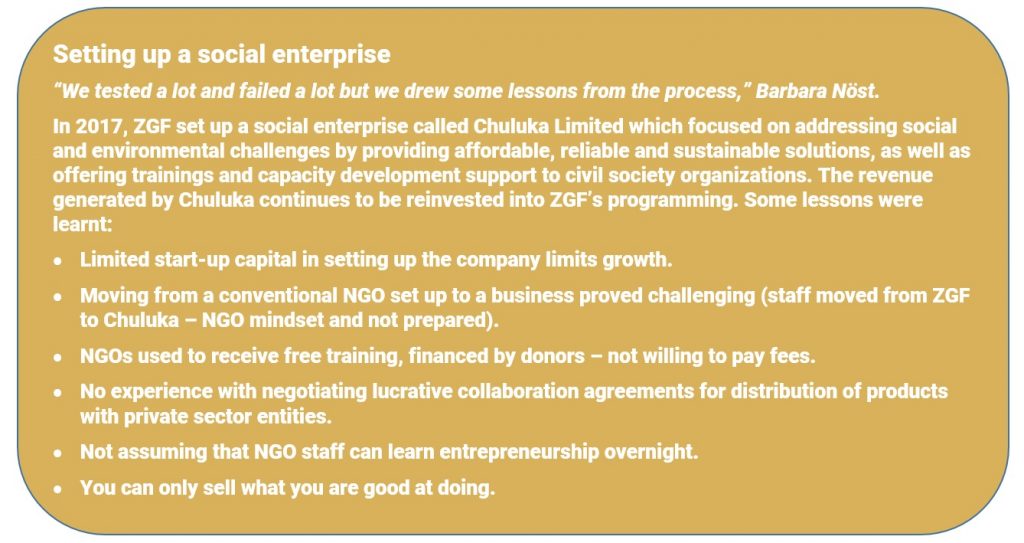

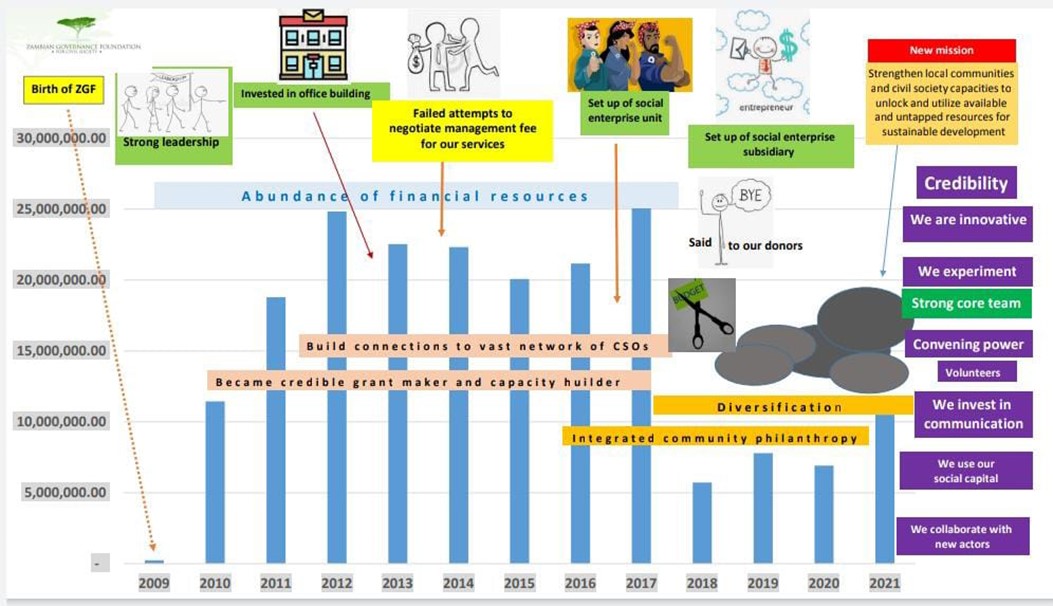

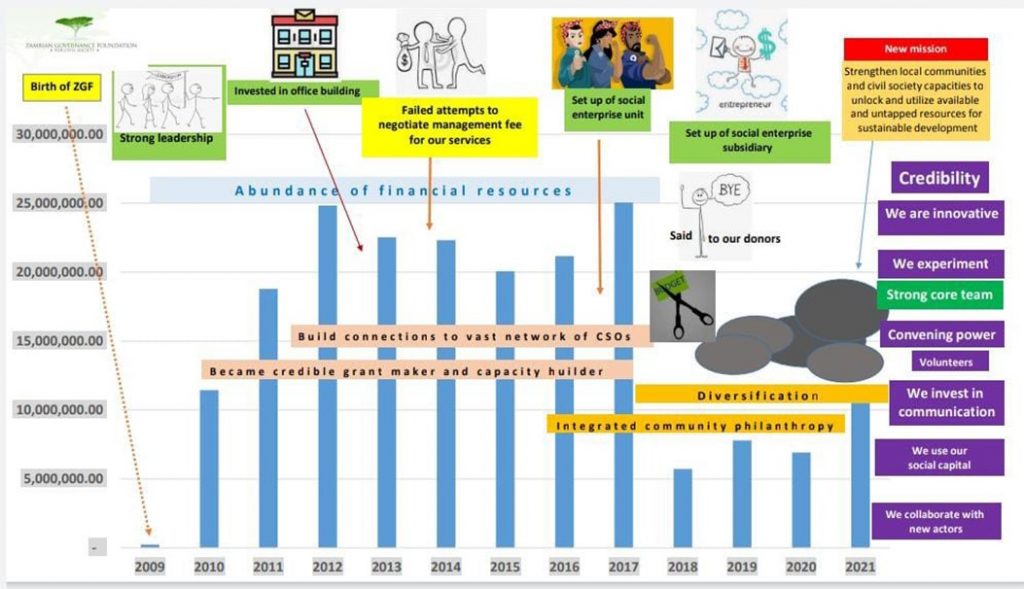

Beyond the discussions that were held by Zambian civil society leaders, two larger conversations which focused on the same topic were convened under the umbrella of the #ShiftThePower movement on 11 May 2022. During the two sessions ZGF, a leading voice in the movement, which has been advocating for a greater focus on civil society financial sustainability, shared the story of its journey from a position of relative financial security (an annual budget of €4 million) in 2009, to one of crisis by 2018 (lessons learnt from ZGF’s experience setting up a social enterprise are included at the bottom of this page):

“Our story is a story of many successes and many defeats, but we have reached a point where we are in a very comfortable space,” said Barbara Nöst, ZGF’s Executive Director. From its inception, ZGF received support from five bilateral donors (the governments of Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Sweden and the UK) which (with the exception of the German government) withdrew their support over time for various reasons. “We always felt that we were never ‘good enough’ for donors: they always complained about our ‘lack of absorption capacity’ and looked at us as an instrument through which to spend money on civil society organizations,” added Barbara.

Fortunately, from the start ZGF always had committed and qualified founders, board members as well as an active Chairperson – all of whom pushed for ZGF’s autonomy. This strong leadership and vision of an alternative future were critical to what happened next.

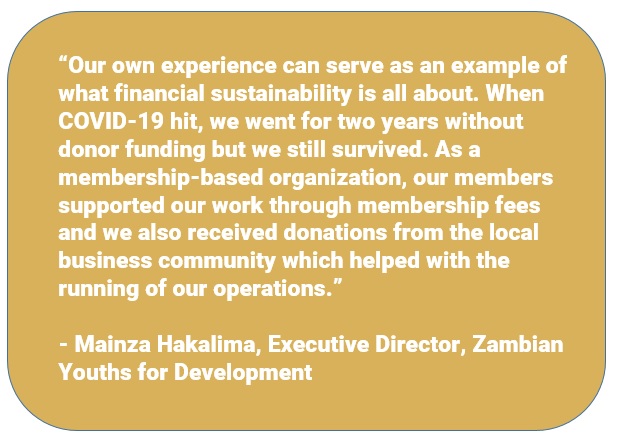

“In 2018, we said goodbye to all our donors. I was happy when we parted ways because there had previously been very little intellectual freedom to design, and I personally felt imprisoned. Between 2010 and 2017, from the outside it looked like ZGF was a well-funded and happy organization, but I have been much happier in the last four years. Having far fewer financial resources has given us freedom and space for creativity,” said Barbara. Since 2017, ZGF has started to chart a new path, building a solid, diversified, local resource base; it has a strong and committed staff and has stronger and more equitable relationships with other community actors.

The deterioration in funding did not only impact ZGF; partners were inevitably affected too. One of these was the Zambia Council for Social Development. Speaking in one of the online discussions in May, its Director Leah Mibita said: “When ZGF’s resources went down, we were given a month’s notice to wind up all of our project activities. Meanwhile, we had staff on running contracts which we could not just terminate. ZGF’s sudden exit had a dramatic and negative impact on the limited resources we had.” This forced the Council to look for alternative ways to fund their work, resulting in a new partnership with an international research board, which allowed them to generate new income and clear their debts.

Resources that make things happen on the ground

Given the financial preoccupations that Zambian civil society organizations continue to face, the discussion series also surfaced a deep recognition and appreciation of some of the more “intangible” assets at their disposal such as trust, legitimacy, reputation, experience and community rootedness.

“We bring different resources to the table, not just money but non-financial ones too. Since all these assets are interconnected, none is more important than the other,” commented George Hamusunga, Director of Zambia National Education Coalition. During the conversations, Zambian civil society organizations reflected on what they saw as their unique strengths:

- “We have a genuine love of our people at the heart of our work and our authentic connections with communities help us to weave and nurture relationships which are not transactional.”

- “We know and understand the local culture and what it takes to motivate people to engage and succeed.”

- “Because we are proximate to and part of the communities we seek to serve, we are better able to surface and help address the issues that communities are faced with.”

- “Equally important, we have better knowledge of the potential and power which exits in communities and we are able to help unleash it for greater impact.”

- “We feel we can legitimately represent the wishes of our people because we are part of them and can relate to their challenges.”

- “We bring a long-term view: if development interventions are going to last, they will always be much stronger when they are designed by and with those for whom they are intended and are embedded in local contexts and norms.”

Resourcing in the new system

Civil society’s reliance solely on international donor funding has never really been practical or desirable and, with the current shifts that are taking place in the funding landscape, new strategies for resourcing civil society work are more essential than ever.

While identifying and harnessing alternative and new kinds financial resources (such as community philanthropy, local cultures of giving, social enterprises etc.) will be essential in any new system, civil society organizations can also get much better at recognizing the other essential, non-financial, resources that they bring to the table – social, intellectual, political, cultural, natural, physical etc. – and to insist that these also get “counted.”

International donors can do their part in helping to prevent the rollercoaster impacts that their funding – and its withdrawal – can have on organizations. Clear exit strategies are part of this, as well as instituting measures aimed at mitigating the adverse effects of programme closures. Funders can also get better at supporting civil society’s efforts to explore alternative funding approaches and hybrid models, as well as to build local constituencies for their work so that their future existence depends on other factors than simply international grants. And, finally, funders can get much better at investing in civil society infrastructure that can ensure that resources reach small and informal organizations and, as part of that, to appreciate the role of local grantmakers not just as intermediaries but as local ecosystem builders.