By: Andrés Thompson, Senior Advisor at ELLAS – Mujeres y Filantropía

This question came to me during a presentation where a group of donors explained the impacts that their small donations had on beneficiary groups. However, there was no talk of how much the contributions of their beneficiaries had impacted on the donors or how much they had contributed to the development of the projects.

In the world of philanthropy, donor foundations and funds – in their variety – are the key contributors. They have the money to donate (it is always repeated that money gives power), so they define the guidelines and issues to which they want their donations to go. They also choose the geographical areas in which they will do so, launch the calls with punctilious details of how to present them – including budgets. These donors also inform the evaluation and accountability processes, they attach a series of moral clauses and policies demanding strict compliance and, finally, demand more details on “counterpart”, such as the contributions in cash and in-kind that the potential beneficiaries of the donations must contribute.

The latter is the reason for this blog. Is this really counterpart funding?

Generally – and even more so in progressive foundations and funds that try to reach the most excluded community groups, the beneficiaries, their families and their ancestors have spent tens, if not hundreds, of years developing survival and development strategies in the most hostile and adverse conditions. Thanks to this, they have managed to stay on their lands even if they do not have property titles, in their jungles although the process of deforestation advances relentlessly, and in their villages abandoned by the state. Women, in particular, have suffered ancestral abuses, they have been victims of gender-based violence, and yet they are standing up for their rights in increasingly brave ways and building from below their “good living.” That capacity, which many call resilience, or resistance, refers to accumulated social capital, often at the cost of great suffering, struggles and deaths. It is precisely that capacity and that capital that is the “starting point” for any development initiative.

Let’s imagine for a moment that the budget of a project and a funding proposal to an international foundation were presented like this:

| Item | Local contributions in USD | Counterpart (international foundation) in USD |

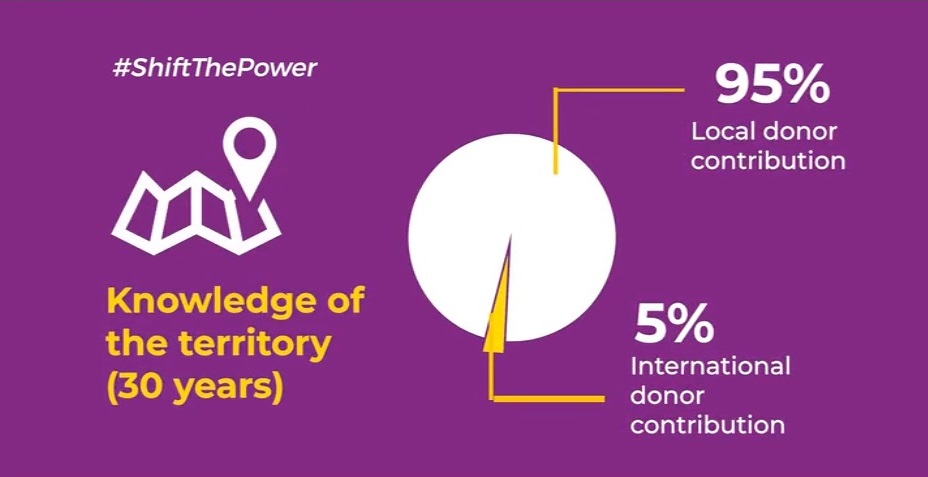

| Knowledge of the territory (30 years) | 200,000 | 100 |

| Participation of local social actors (time for talks, negotiations, visits, meetings) | 150,000 | |

| Human resources (activists, volunteers, leaders, trainers) | 300,000 | 30,000 (payment of partial salary) |

| Materials and equipment (meeting rooms, houses owned by community residents, bicycles, motorcycles, cell phones etc.) | 100,000 | 10,000 (contributions for a computer and printer) |

| Administration | 40,000 | 10,000 |

| Travel (in own vehicles, on walks, in cars etc.) | 40,000 | 5,000 |

| Total | 830,000 | 55,100 |

In this case, as in so many others, the counterpart funding would be much lower than the local contribution. Surely the donation of USD $55,100 would be greatly appreciated, but the reverse would not be acknowledged. When donors demand that their beneficiaries provide “counterparts” they are in a way subverting historical processes and constructing an erroneous narrative. The “counterpart funding” is from the donors and not from the locals. Possessing financial resources to donate, that give “power”, should not be a justification that prevents humility and respectful relations. External resources are only a modest contribution to the gigantic efforts and contribution that the communities make daily. They are the “starting point.” Without it, there is no possible development project.

Andrés Thompson is a Senior Advisor at ELLAS – Mujeres y Filantropía

A version of this article was originally published in Spanish and by Alliance Magazine in English.