Have you heard of imaginal cells? This is what Amaha Selassie asked us as we sat in the jungle-themed hotel lobby. It was the night after the #ShiftThePower Summit in Bogotá, and 5 of us had come together seemingly by accident, talking for hours about the worlds of possibility and complexity that the Summit had unlocked. None of us knew about these cells, so Amaha explained:

When a caterpillar enters the chrysalis, it begins to digest itself and becomes a mush of parts. The imaginal cells, dormant until now, start to multiply. At first these cells function independently but, as they divide into clusters, they start to resonate at the same frequency and exchange information. Despite attacks from the caterpillar’s immune system – mistaking these cells for a foreign threat – the cells keep dividing until they reach a tipping point and form the structure of a multicellular organism, the butterfly.

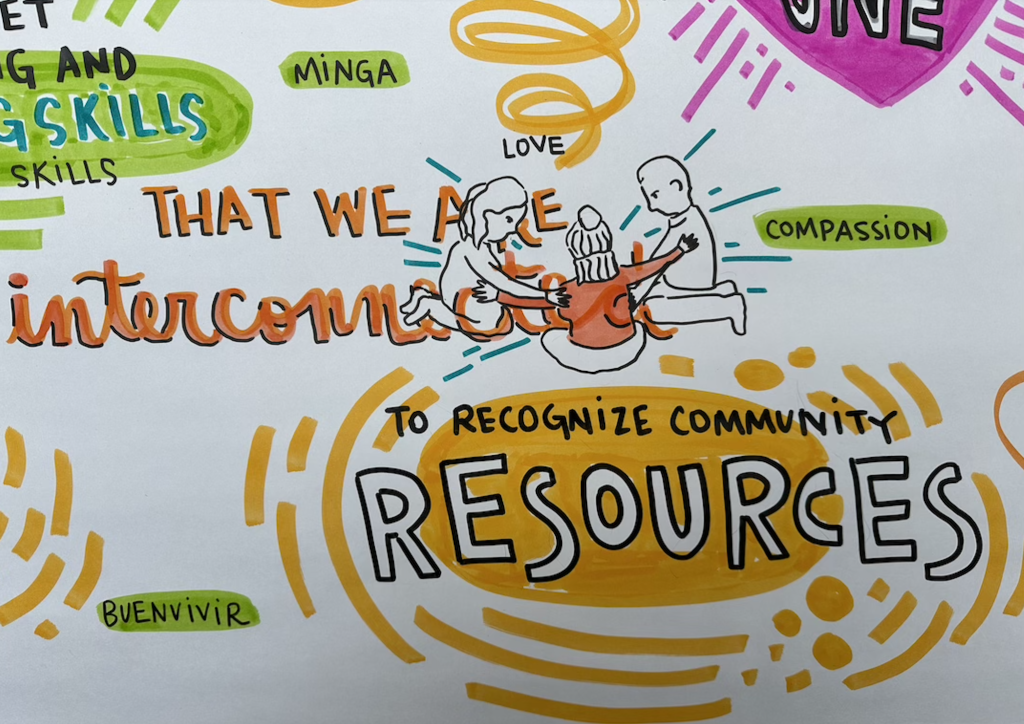

We’re the imaginal cells! Amaha said grinning. And that is how we felt post-Summit: suddenly aware of the many clusters transforming their communities, and all of us coalescing around simplistic, outdated structures in order to make them into something more just and capable.

After returning from Colombia, I went back to the start where many of these seeds were planted: the weaving conversations on The Road to Bogotá. These discussions explore how to deconstruct inequitable systems, understand what is no longer serving communities, and what it might look like for aid, development and philanthropy to undergo its own metamorphosis.

Here are a few of the themes that stand out from these conversations, and what they tell us about the way forward.

Simplicity to complexity

The Measuring what matters: bridging scholarship and practice webinar explored the gulf between traditional metrics and what matters to community foundations and their local partners. Donors tend to ask grant recipients to measure a discrete project’s basic indicators (outputs, activities, the amount of money spent) – a focus akin to looking at a complex organism through a single-celled lens. “Those easy measures felt very meaningless to us as they demonstrated just actions rather than progress,” said researcher Dana R.H. Doan. “At the same time…regularly meeting in person and exchanging ideas, that was being seen by some of our stakeholders as an inefficient use of resources.”

You have to trust the process without controlling it. This is really the essence of power and letting go…Moving with and where the energy is. Because only then can you really see those things that percolate up to the surface that matter. – Ese Emerhi, Disrupting colonial legacies of philanthropy in Africa

Community foundations and partner organizations focus on building relationships in order to understand the many factors that shape communities, rather than leading with a project or donor-defined targets. In the webinar on Connecting climate justice and community philanthropy, Artemisa Castro Félix from Fondo Accion Solidaria (FASOL) shared: “Community foundations are often considered intermediaries in the global development space, but we are much more than this.” From the perspective of communities, she said, “community philanthropy is a practice of solidarity and support that exists between communities and collectives.”

When Karima Kadaoui of the Tamkeen Community Foundation for Human Development is meeting with communities, she starts with a clarification: “‘we’re looking for partners, we’re not looking for funding.’ That changes the conversation.” This emphasis on collaboration is a small but significant shift away from what donors often incentivize and towards an emergent, co-created process. “How can this relationship, this partnership,” Karima asked, “reflect why we are coming together to do what we are doing?”

Given that logframes do not account for relationship-building, how is donor demand for quantifiable outcomes affecting the freedom that organizations have to partner with communities? “I have two main worries about evaluating social impact for social change organizations,” Professor Lehn Benjamin said in Measuring what matters. “The first worry is that evaluation will actually exacerbate inequity rather than help address it. The second is – and this is why I think it might happen – evaluation seems to undervalue relational work.”

Given that logframes do not account for relationship-building, how is donor demand for quantifiable outcomes affecting the freedom that organizations have to partner with communities?

When it comes to social change, undervaluing relational work is not only a disembodied approach, it also implies that partners who prioritize our shared humanity – and communities themselves – are less valuable. What does this discriminatory yet pervasive perspective say about the balance of power in our sector?

Power in the people

In Decolonizing International Cooperation, Ambika Satkunanathan with the Neelan Tiruchelvam Trust spoke about the inherent conflict at the heart of our work: “The crux of aid and grantmaking is that it is those who have the resources provide resources and assistance to those without. Hence the very foundation…is built on power disparity.”

This imbalance perpetuates the perception that those who control the world’s resources are the rightful power brokers, but as Jenny Hodgson of GFCF said in the Connecting climate, “we don’t often acknowledge resources that already exist on the ground.” Global Greengrants Fund shared that, while international funding for climate mitigation has tripled since 2015, it only constitutes 2% of total funding. The amount dedicated to the intersection of human rights and climate justice is even more limited, with women’s environmental issues receiving less than 0.02% of total funding, and between 0.01% – 0.03% going to indigenous communities.

Who has the power is not transferable. I think we have to recognize that power has always been in the people. – Artemisa Castro Félix, Connecting climate justice and community philanthropy.

Despite the woefully inadequate financing, communities and their local partners continue to adapt to rapidly changing environments with ingenuity. “Why is it that community foundations are ignored by climate funding?” Laura Garcia of Global Greengrants Fund asked. “One of the tendencies of climate donors is they think in terms of scaling up. They don’t believe that climate solutions are actually a million different local solutions. We need to be the ones organizing this space…for this money to spread out individually and come like a rainfall.”

When donors are guided by a narrow focus that obscures the bigger picture, their funding rarely has a lasting impact. Ambika put it simply: “International aid and grantmaking tackles only the symptoms, not the causes.” Many donors don’t see, and therefore don’t adequately support, local solutions if they are only looking for symptoms. So why are symptoms the focus and not the causes? Because this focus is easier, Ambika said, and because “tackling the root causes also requires you to confront the fundamentals of these very ecosystems that all of us inhabit, and the processes that we use. This requires holding a mirror to oneself.”

Languages ancient and emergent

Holding up a mirror invites curiosity about ourselves and the roles we play, and have historically played, in this ecosystem. It is not surprising that the language of aid, development and philanthropy reflects traditional decision-makers from the Global North more than those from the Global South.

“Communities don’t know the word philanthropy let alone community philanthropy,” Artemisa Castro Félix shared, “but when we talk about the importance of recognizing all the resources that we have to develop our projects, they realize that they have everything in their hands to achieve it.” Artemisa said that community members often add: “if you don’t give me the finances, it doesn’t matter to me because I’m going to do my project. The only difference is the time in which I will do it” (Connecting climate).

The wording is important to the extent that it is actually creating more of a gap between the players who matter as opposed to bringing them closer together. – Themrise Khan, Decolonizing International Cooperation

How these community members relate to their projects is a far cry from the way most international NGOs and donors engage with initiatives. Artemisa’s example reflects the ubuntu philosophy, a worldview that Olabukunola Williams from Akina Mama wa Afrika summarized as “I am because you are. Seeing our liberation as deeply tied and connected and rooted to each another.” (Decolonizing efforts in philanthropy: experience weaving.

Changing or reclaiming language opens the door to a shift in perspective and entirely new ways of understanding each other. Karima Kadaoui described how communication evolves along with Tamkeen’s partnerships: “in that process of experiencing and reflecting with our [community] partners what was experienced, a language started growing; the language of objectives, impact and indicators started dissolving” (Measuring what matters).

When we invite what is emergent to shape these partnerships and collaborations, our identities can shift too, allowing that interconnected reality to supplant static ideas of ourselves and one another. Karima’s example is also a reminder that the process has its own value. Returning to imaginal cells, a butterfly is possible because the organic process of metamorphosis is not limited by efforts to control for specific characteristics. It is an emergent transformation that cannot be predetermined, involving every aspect of the caterpillar in the process.

The past in the present

There are many colonial pasts actively shaping our present, from the ways we speak to how we tell our stories. In Decolonizing international cooperation, Dylan Mathews of Peace Direct gave the example of localization: “where people don’t want to talk about shifting power or decolonizing, they talk about localization and they conflate the terms. What we might be hearing is a white-washing of change by calling it localization when actually it needs to be much deeper than that.”

Going deeper involves what others have already shared – self-reflection, relationship-building, seeking root causes rather than surface symptoms – along with an honest accounting of whose interests are prioritized. As Nadia Ahidjo at the African Women’s Development Fund put it: “A colonial legacy we have is that we [in philanthropy] don’t necessarily think about accountability to our movements; we think about accountability to whoever is paying, whoever is giving the money” (Disrupting colonial legacies). In systems where collaborative processes are undervalued and local solutions are poorly funded, it follows that accountability mechanisms are built to serve Global North donors and INGOs first and communities second.

What makes me feel optimistic is not the intellectual exercise of decolonization, but the heart exercise of decolonization. – Dr. Amber Banks, Decolonizing efforts in philanthropy

“In order to be accepted into the global grantmakers club,” Ambika Satkunanathan said, “we may feel the need to adhere to processes that are inequitable and reproduce the dysfunctionality for which we critique international donors. Mimicking international donors leads to what I call ‘trickle-down inequality’ in the guise of achieving social justice. Hence what this requires is decolonizing the mindset – even our mindsets” (Decolonizing international cooperation).

We all have a colonized mindset. Unraveling this is not only a life’s work, but also intergenerational, embodied and can only be transformed together. What we build in its place requires us to be, as Ese Emerhi put it, “comfortable with discomfort, comfortable in abstractness. Because we are dreaming of a future that we can’t quite actualize yet, we can’t quite see” (Disrupting Colonial Legacies).

Co-flourishing

After a recent collaboration with a community partner, Karima Kadaoui described how everyone involved was changed by the experience. “We went from thinking the one, individually, to thinking together, the community. We went from objective to process. [The community] said, ‘today we are experiencing what we call co-flourishing.’ We are all growing together in understanding what does it mean to trust our humanity” (Measuring what matters).

Many of us may have glimpsed this in our work: an experience of interbeing that expands our perspective and nourishes our shared interests. It is, however, far from a common experience. How do we get closer to co-flourishing? As Masarat Daud of Adeso said, “the norms are so deep-set. People are at different levels of decolonization” and dismantling other abuses of power (Decolonizing international cooperation, 2nd session). How can we move forward together if we are at various stages of transformation?

When Amaha first mentioned imaginal cells, I saw them working in sync like many surgeons operating around the same table. After revisiting these webinars, I still envision them working in tandem but on a myriad of local transformations that may seem separate but collectively tip the balance. “Decolonizing isn’t just an act of dismantling,” Dylan Mathews said. “It’s also very importantly an act of reclaiming and rebuilding. If we only look at the dismantling side, it can be quite a negative framing for what I think is a radical proposition for changing the way in which the system operates.”

What does collective action look like if some of us are undoing, some are repairing and others are rebuilding? When this question came up in the Connecting climate webinar, Jenny Hodgson responded: “We all operate in a competitive system which doesn’t facilitate trust-building…If we know that we’ve got allies and colleagues that have the technical expertise, then we don’t all need to be experts. We need people to be angry, we need people to be strategic – that’s how this will work.”

We should be uplifting our knowledge, our narratives, our voices without having to prove that we’ve done something amazing so that somebody somewhere will give us money. – Nadia Ahidjo, Disrupting Colonial Legacies

Along with trust, Madonna Vicky Ainembabazi at CivSource Africa sees centering solidarity as another key difference in this emerging system. “Traditional funding is more transactional. Decolonized philanthropy would be the more relational kind of philanthropy that values solidarity over conditionality” (Decolonization efforts in philanthropy). With solidarity comes a sense of urgency. How could we not feel that we are racing against time to build representative systems with redistributed power? But Dylan Mathews offers a warning: “If you try and make changes to practice quickly without changes to mindsets and worldviews and attitudes, you’re going to fail.”

Dylan and Peace Direct focus on building bridges instead of fast-tracks, such as encouraging INGOs to adopt a transition mindset. This involves asking questions like: “Why [is our] strategy predicated on growth, and [why are we] doing more when actually we should be doing less and shrinking our role? Why are we producing and consuming knowledge when we could be investing in knowledge production and consumption in communities?” (Decolonizing international cooperation, 2nd session)

From the perspective of the African Women’s Development Fund, it’s about exploring partnerships that fall outside of traditional parameters. “Before, we used to work with registered organizations,” Nadia Ahidjo said, “you had to have financial audited statements – you know, all the things – and now it’s really about working with what we call movement entities.” By broadening their collaborations to include artists and activists, there is greater representation of who is locally engaged in social transformation “without them having to fit in that NGO box” (Disrupting Colonial Legacies).

People don’t want to talk about shifting power or decolonizing, they talk about localization and they conflate the terms. What we might be hearing is a white-washing of change by calling it localization when actually it needs to be much deeper than that.

For CivSource Africa, decolonization has been a reimagining process that Madonna described as “tackling the colonial attitudes we didn’t even know we had, both at a personal level but also at an organizational level. By virtue of our positioning as an advisor, a grantmaker and implementer, we had the advantage of shapeshifting to get some people in the room that we would not have typically convened if we had only existed as an NGO” (Decolonizing international cooperation).

At the Decolonizing Wealth Project, Carlos Rojas Álvarez shared that decentering the donor is key. “We have over 625 donors, and none of them have decision-making power. We say to them, you give us the resources and communities get to decide where those resources go. When we say liberated capital, we don’t just mean liberate the capital itself for the recipients…we’re also talking about liberating capital holders from the need to control.” While Carlos acknowledges that not all funders are open to this process, he said wherever you can invite them in “and paint a clear picture of how decolonizing wealth is actually good for all of us in the long run, that’s where we’ve seen traction with donors” (Decolonizing international cooperation).

But what about the real possibility that aid, development and philanthropy are too broken to be meaningfully transformed? “When is [philanthropy] maybe going to die,” Olabukunola “Buky” Williams asked, “and something else is going to rise like a phoenix from the ashes, for us to really be able to come back to ourselves? For us to truly be able to build the communities and systems that help us see each other as not disposable, or as somebody who needs help and I’m here to give you help” (Decolonization efforts in philanthropy).

Buky’s last point is one that Karima Kadaoui also identified: seeing ourselves as separate is holding us back. “Dissolving this duality,” Karima explained, means “no longer needing to find the value because [this new system] trusts that whatever the community does has a value. We are coming together in co-reflection, growing a shared understanding, and that very process…is transformative” (Measuring what matters).

Similarly, Indonesia for Humanity (IKa) is breaking away from the binary with a new approach to monitoring and evaluation. Determined not to replicate “the suffocating working model of many donors”, IKa created a method for measuring progress called pemaknaan: the act of giving meaning. “The purpose of pemaknaan,” Meiska Irena Pramudhita shared, “is to cultivate an understanding of social transformation efforts by the grant recipients. It’s not meant to assess the outcomes of the work…We want to see how it manages to propel the social transformation without assessing the progress in terms of success and failure” (Decolonization efforts in philanthropy).

Each of these developments, thanks to creative experimentation and risk-taking, move us closer to co-flourishing. But a question from Karima remains: “How can we evaluate an organic and emergent process without being in the way of the process?” This doesn’t apply only to evaluation, but to all aspects of this metamorphosis: how do we know when we are facilitating positive change, and when we are just in the way?

Sometimes one of the biggest hurdles to action is the need for certainty. If we are imaginal cells, and I believe that members of this global movement are, we can’t see what these future systems will be because we are in the midst of co-creating them. What we can see is where we are on the continuum of transformation, and we can recommit often and together to accessing curiosity, inspiration and non-duality within ourselves, our communities and our movements. Thanks to these conversations and the Summit, I am experiencing a newfound trust in this process because I trust this movement. And that feels powerful.

Kate Cummings is the Transition Director at The Lotus Institute and Associate at Tsunagu.