When I was in grad school, there was a strong push to limit overhead expenses to just 10%. This movement argued that 90% of an organization’s budget should go directly into project activities. However, this perspective was primarily aimed at international non-governmental organizations (INGOs). It was often assumed that local organizations needed the same restructuring, even though they operate differently from INGOs. This assumption led to the imposition of INGO-style due diligence processes on civil society and community-based organizations, causing stress and anxiety when seeking funding opportunities.

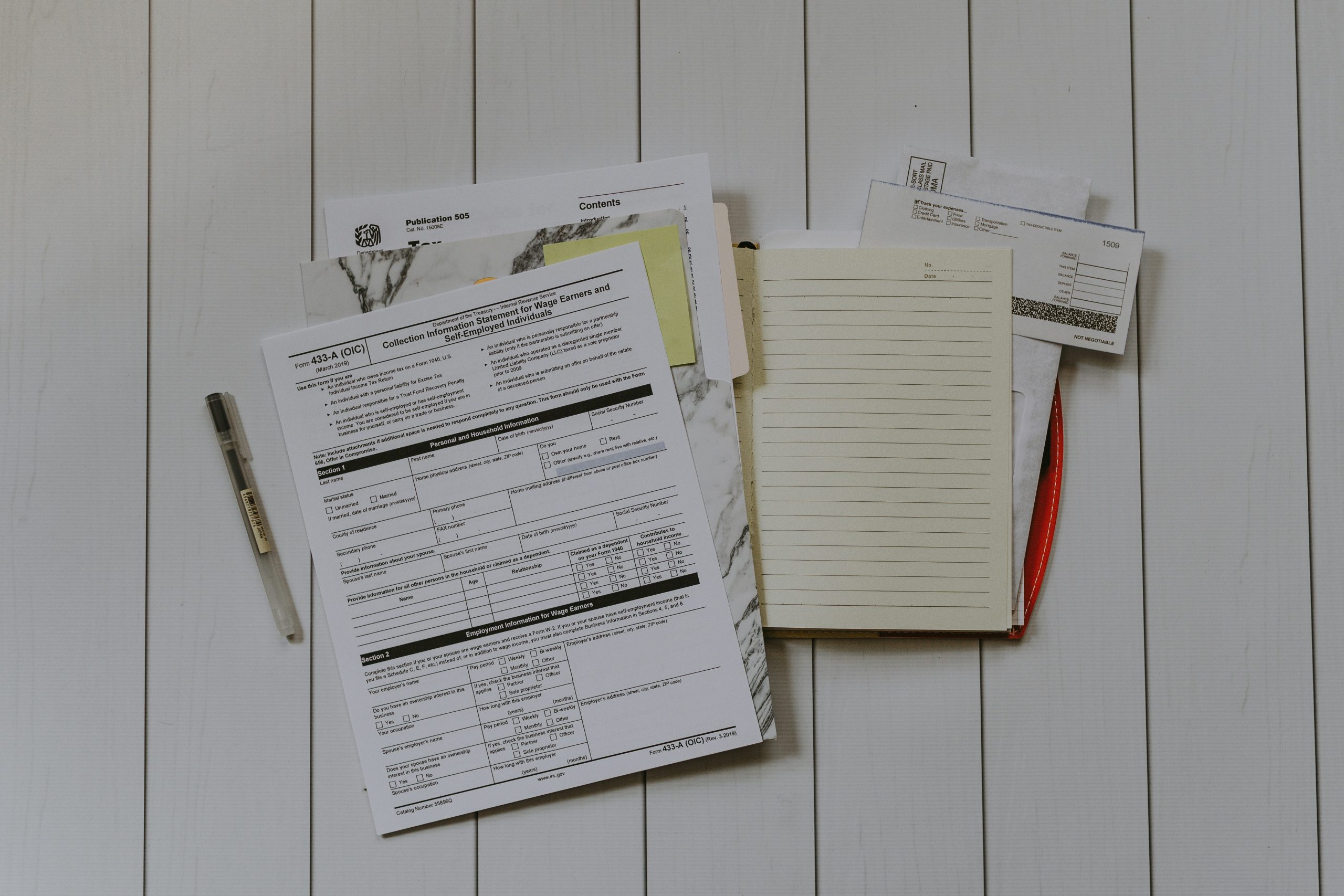

Why does due diligence create such stress and anxiety? To answer that question, we must understand what it involves. As a requirement imposed by funders, its formats can vary widely. For example, bilateral funding sources such as USAID have stringent requirements, which may include retaining paperwork for up to seven years and the responsibility of finding storage space. Many who have experienced various forms of due diligence feel frustration and anxiety because the process is a one-way examination into the inner workings of local civil society organisations, and starts from a position of distrust.

Equitable Partnership

Let’s shift our focus away from civil society organizations (CSOs) for a moment and consider the private sector. Whether it’s a large corporation or a small company, when entities aim to merge or colloborate, both parties engage in due diligence of some form of assessing whether they can trust each other. This critical aspect of trust-building often goes unmentioned yet it must occur on both ends.

Many who have experienced various forms of due diligence feel frustration and anxiety because the process is a one-way examination into the inner workings of local civil society organisations, and starts from a position of distrust.

However, challenges arise from an entrenched power dynamic where it’s assumed that one party gives, and the other receives. This understanding is fundamentally flawed because both funders and grantees provide essential services, Cash from international funders is never enough to do development work in communities without local networks, social capital various other local resources. As CSOs, we must adopt an approach that involves performing due diligence on why and how funders support our organizations. Recent efforts by the #ShiftThePower Movement to conduct a “reverse due deligence” on Global North governments that fund civil society have shown that only 10% of international funding goes to Southern CSOs directly. In all this, funding relationships start from a position of distrust towards Southen CSOs. At the core of conversations to reform due deligemce, we must also answer the question on how we want to assess and establish trust in the international aid system.

Due diligence in complexity

Even progressive funders, who are keen on reforming due diligence, tend to seek standardized approaches, and there is a danger in this. The only standardization necessary should be the fundamental requirements that funders must meet to comply with their respective countries’ legal obligations, which we cannot alter. However, even strict legal compliance isn’t always feasible, depending on the country’s context. In such cases, advocacy work becomes essential to change these laws, thereby reshaping the nature of compliance to fit the context in which it is happening.

In rethinking due deligence procedures, our approach needs to reflect reality and be tailored to specific contexts. The compliance challenges encountered by organizations in Ethiopia, for example, are markedly different from those faced in Bangladesh. When funders hold significant power, they must also bear the responsibility of understanding the challenges and requirements of the civil society organizations they support. This is where funders should question whether their involvement is merely a transaction or the building of a genuine relationship. If we lean towards the latter, it necessitates effort from both sides. By creating room for humility and a willingness to learn, we can develop more effective solutions. We should be open to reflecting on the fact that what we once considered the best solution may no longer be serving its intended purpose in its current form. Remember, nothing that’s created remains perfect forever. We need another system to do due deligence.