By Jimm Chick Fomunjong

This blog post first appeared on the Global Fund for Community Foundations on July 6, 2021.

3rd June 2015 remains a dark day for Ghanaians. This sad day was marked by a deadly flood caused by heavy torrential rains and a ghastly fire explosion at a filling station that claimed the lives of over 200 people in Accra (Acquah, 2017). Many were left in rage by the agony caused by the explosion of this filling station. Over 46,370 people were affected with about 187 houses partially or completely destroyed (Ibid).

The situation caused pandemonium in Ghana and the world at large. Ghana was hit by one of the deadliest unexpected disasters in the history of the nation.

Amidst the chaos, Ghanaians braved the storm. Citizens aided the fire service to minimize the losses by putting off the fire. Citizens also assisted ambulance services to convey the lucky survivors to nearby treatment facilities.

Furthermore, Ghanaians, government agencies, corporate bodies, and civil society organizations were at the forefront of mobilizing resources locally to support survivors of this deadly incident.

For example, eight days after the incident, a collaboration between Citi FM, Metro TV – two leading media institutions in the country – and Fidelity Bank, mobilized resources that enabled them to provide relief items to some 8,000 persons who were woefully affected by the incident. They further mobilized 25,000 Ghana Cedis (approximately $5,000 USD) which they donated to the National Disaster Management Organization (NADMO) for onward disbursement to victims of the flood and fire disaster.

Also, Omni media donated 25,000 Ghana Cedis to NADMO to assist victims of the disaster. The Petroleum Ministry also donated 1.45 million Ghana Cedis to victims of the disaster.

The twin disaster attracted support from some neighboring countries. The Republic of Benin, through its ambassador to Ghana, donated $200,000 USD to assist those affected by the disaster.

Overall, the victims were supported largely through humanitarian aid mobilized mainly in Ghana.

The response to the 3rd June twin disaster in Accra is one of many such unheard-of responses steered in the global south despite their resounding gains in enhancing the quality of human lives and promoting human dignity.

It is obvious that humanitarian aid, whether globally or locally driven, contributes to save lives and alleviate the suffering of victims of disasters. When disasters strike, local actors or organizations play a key role to respond to them almost immediately. Locals have direct access and network to meet the needs of those who have been affected by disasters. They know and understand the local context, hence can quickly identify and respond to urgent humanitarian needs. It is therefore without a doubt that local actors are a key instrument needed to sustain humanitarian responses.

However, donors seem to have failed to recognise and wholly appreciate the crucial place and role of local organisations in delivering direct response actions to victims of humanitarian disasters.

However, donors seem to have failed to recognize and wholly appreciate the crucial place and role of local organizations in delivering direct response actions to victims of humanitarian disasters. This can be deduced from the meager resources allotted to local actors to counter the challenges posed by disasters or, more broadly, development challenges facing their communities.

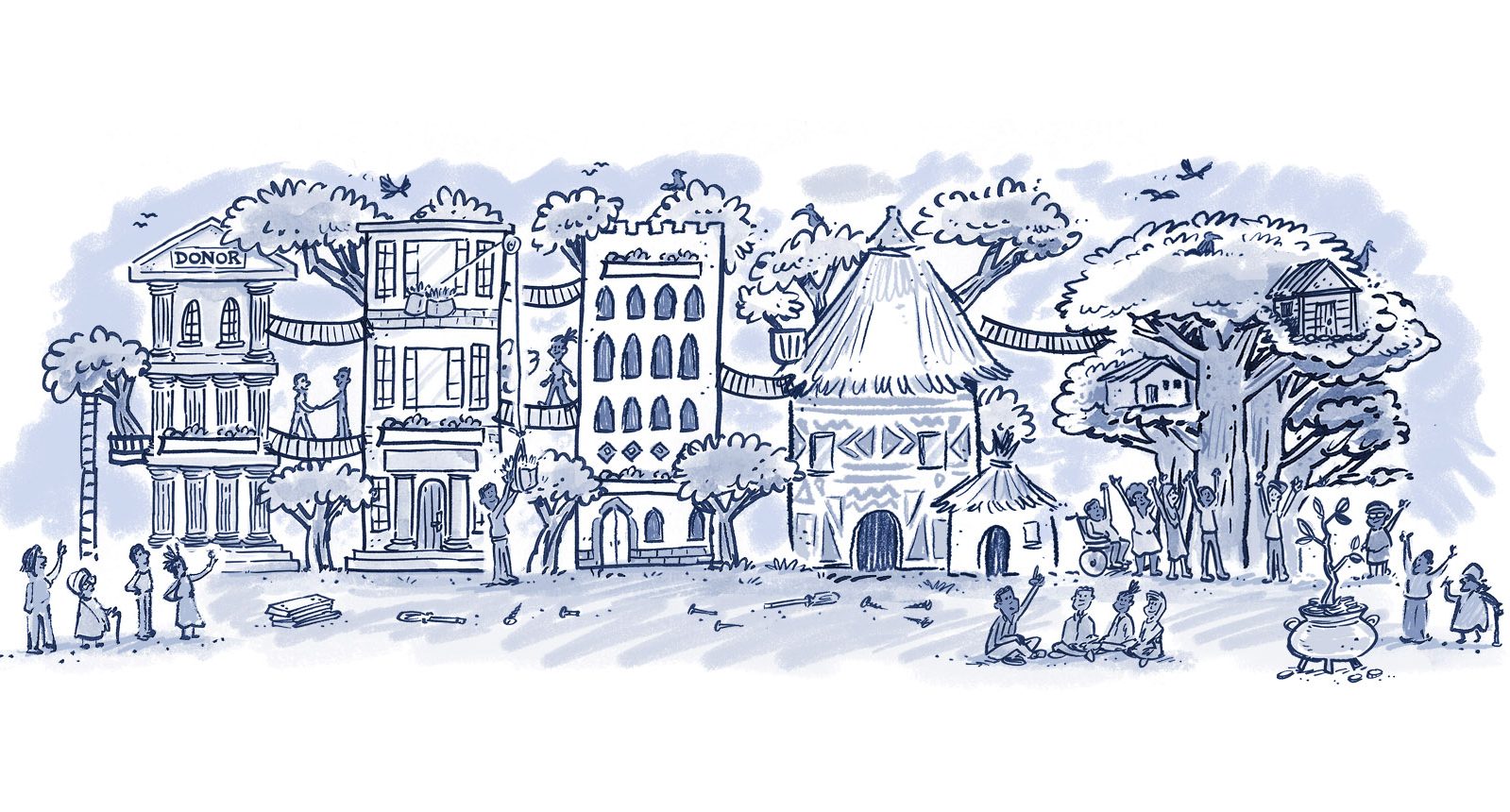

A significant proportion of humanitarian aid is being channeled, either through international non-governmental organizations (INGOs), a multilateral agency, and or a United Nations (agency before reaching local organizations like NADMO. In some cases, the funds are sub-granted to local organizations while in other instances, humanitarian support programs are sub-contracted to local actors, or worst off, local actors are used as implementing agents. Hence, the intermediary donor system.

This approach of delivering humanitarian aid breeds inequality which does not favor local organizations. It does not fully promote equal partnerships between INGOs and local actors. Also, it has not sufficiently ensured better coordination with local coordination mechanisms.

Furthermore, such a mechanism undermines the relevance of institutions like NADMO in Ghana and or other civil society organizations in the global south who are at the forefront of responding to disasters when they happen. The intermediary donor system further cripples local institutions, rendering them somewhat irrelevant or making them to be weaker vessels or underdogs in times of crucial humanitarian disasters that require their full responsive exuberance.

This is largely precipitated by the resource incapacitation of local actors. Given that INGOs and other intermediary actors are sufficiently resourced, they flaunt their resources to determine the pace with which local actors have to respond to the crises in their communities. They hold powerful levers to drive this and direct the localisation agenda to a trajectory that suits their interests

This is largely precipitated by the resource incapacitation of local actors. Given that INGOs and other intermediary actors are sufficiently resourced, they flaunt their resources to determine the pace with which local actors have to respond to the crises in their communities. They hold powerful levers to drive this and direct the localization agenda to a trajectory that suits their interest, some of which are perceived to align with neo-colonial interests.

Also, donors and INGOs have the money. And given that money is power, they wield the power indiscriminately, giving less consideration to those whom the money is meant for.

As Mark Lowcock, United Nations Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator explains: “Despite good intentions, the humanitarian system is still set up to give people in need what international agencies and donors think is best, and what we have to offer, rather than giving people what they themselves say they most need.”

To address such, instruments such as the Grand Bargain Agreement, launched during the World Humanitarian Summit in May 2016, were put in place to facilitate access to resources by those who need it most. Specifically, it aims to ensure that an aggregate target of 25% of global humanitarian funding is channeled “as directly as possible” to local and national responders by 2020.

Is this happening? Unfortunately, not!

So, what way forward? Read part two of this series for more.