A conversation with Moses Isooba and Sarah Pacutho, Uganda National NGO Forum

In 2021, Ugandan civil society was being beaten on multiple fronts. As the pandemic forced lock-downs, the country faced simultaneous crises in health, general elections, and the economy.

Just when it seemed things couldn’t get any worse, the government attacked the NGO sector – suspending the Democratic Governance Facility (DGF), the funding stream for NGOs, suspending 54 NGOs due to “non-compliance” with the NGO Act 2016, and freezing the bank accounts of the Uganda National NGO Forum and the Uganda Women Network (UWONET) on patently false allegations of financing terrorism. Such government action to close civil society space is increasingly common across much of Africa and the world as governments fear infiltration by foreign agents and attempt to take control.

Over the past decade — which is about the same period within which the flames of civic space have raged across and beyond democratic and authoritarian political landscapes alike — governments, corporates, and intersecting interests have deployed legislation, administrative fiat, economic measures, and outright force to attain their nefarious ends.

As the annual State of Civil Society report for 2020 has found, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated, accelerated, and further exposed crucial global challenges that were at the fore in 2019, not least restricted civic and democratic freedoms, economic policies (like austerity) that fail most people, widespread exclusion, limited international cooperation, and a failure to follow the science and act to ameliorate the global emergency of climate change. The report’s findings are explicit:

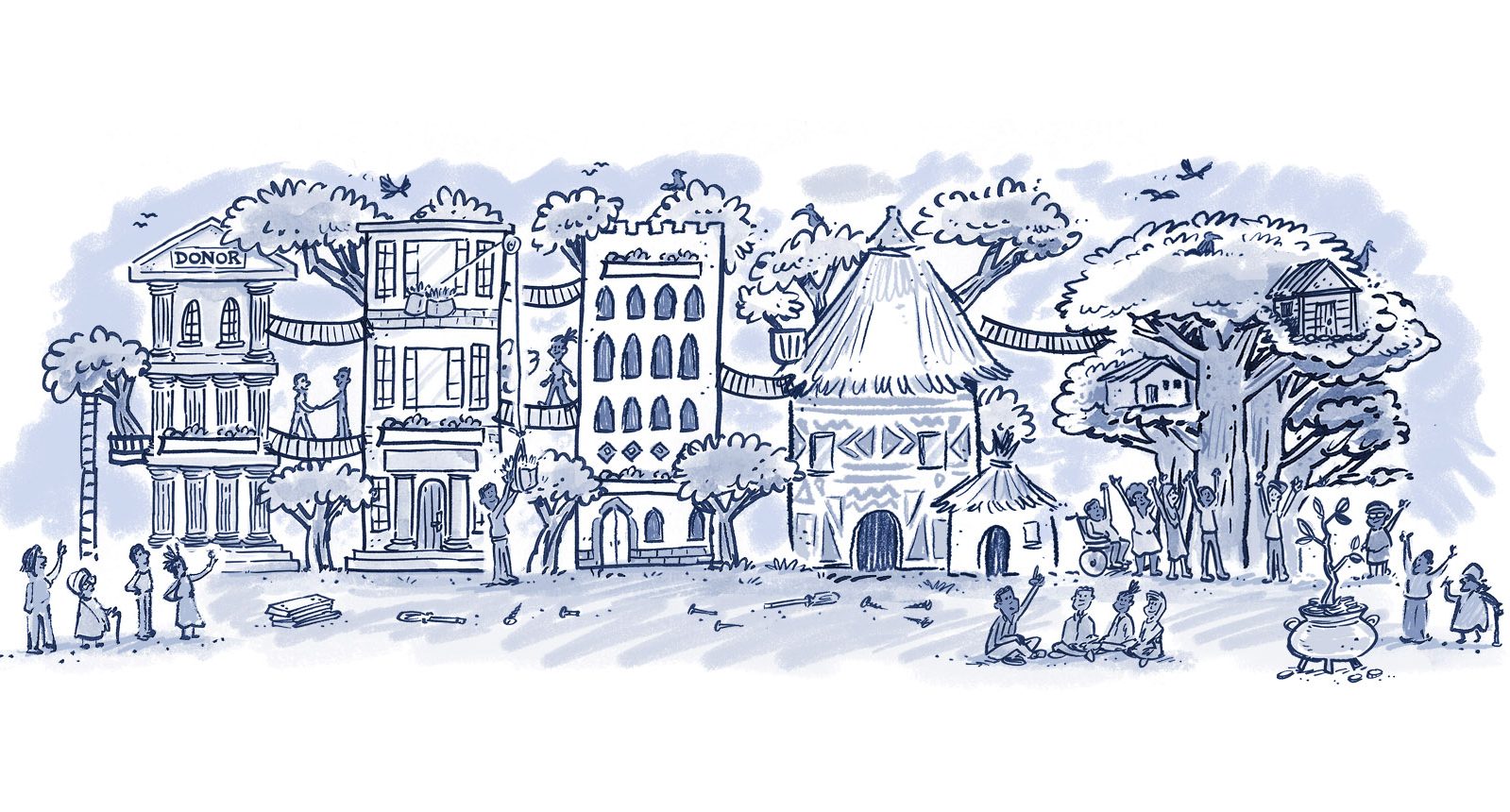

Despite the aggressive shrinking civil space in Uganda (the Civicus Monitor ranks Uganda as “repressed”), civil society appears to have shown a remarkable turnaround in recent months, re-imagining how development should be done by building a new ecosystem rooted in local community action. The new approach is already yielding dividends.

To find out more, Ese Emerhi (Global Fund for Community Foundations) and Barry Knight (independent measuring and learning consultant) caught up with Moses Isooba, Executive Director, and Sarah Pacutho, Team Leader for Civil Society Strengthening, from the Uganda National NGO Forum. They wanted to find out what new insights and reflections have come out of implementing the Giving for Change program in its first year of programming, and what their vision and hope for a re-imagined development sector for Uganda is.

BK: You talk about a new approach to doing development differently, a re-think if you will. What made this happen?

MI: In the face of such threats to civil society, it was clear that a new approach was needed. Money from outside donors was no longer an option because it ran the risk of local organizations becoming classified as foreign agents and would lend itself to the government’s dominant narrative that NGOs are “foreign-funded proposal writing outfits”. The answer was to leverage the current appetite for community-led development and raise local resources. So, whether we’re calling it community resource mobilization, domestic resource mobilization, or philanthropy, we decided that this was the way to redefine development and to prove to the government that we are not a foreign agent. Whether one refers to this as localization, locally-led development, community-led development, people-led development, #ShiftThePower, or something else, it’s time for the Global South to touch the reset button.

EE: What has the Giving for Change programme meant for the work of the NGO Forum and Uganda more broadly?

SP: The Giving for Change came along at exactly the right moment. At the start of the program, we had to change the name of the program from Giving for Change to Philanthropy for Development due to sensitivity with the government around language and certain words that triggered resistance.

As part of the program, the NGO Forum produced five ‘sense making’ policy briefs on philanthropy covering the themes of 1) Meaning and Practice of Philanthropy; 2) Nexus between CSOs and Philanthropy in Uganda; 3) Philanthropy and Foreign Aid; 4) Giving with the Head or with the Heart, and 5) The Shadow Side of Giving.

These reports were an opportunity for us and our community to assess what philanthropy means, and how this relates to giving for development as opposed to charity. The reports also enabled us to test out various models of giving. This work enabled us to assess whether a community-driven approach was viable, and we found that it was. For example, we heard stories of how a community came together to problem solve and contribute to solar panels being installed in the Community Health Centre for improved service delivery.

BK: What has been the result of this new way of working and organizing with your partners and the communities you work in?

MI: As a result of the changes, a new civil society ecosystem has developed. Not only has this found a new role in the polity, but also its methods are yielding dividends on the ground.

A keyword is “connection”. Civil society is beginning to join up its efforts and become a seamless ecosystem. The program has allowed us to change interventions depending on the need on the ground. Local actors are now able to connect with national actors, forming relationships built on trust, which produces bigger results. We play a connector/facilitator role in this way, sharing our resources, networks, and power.

A keyword is “connection”. Civil society is beginning to join up its efforts and become a seamless ecosystem.

This has meant local organizations are now playing the role of collaborators. One realization from this work is that no organization or sector is sacred; we all must work together if we want to succeed. The conversation must happen with all stakeholders together. The result is that donors are realizing that they need CSOs. Such considerations also apply to INGOs who face a choice – either you give up (or share) power willingly or you are compelled to give up power. Only three scenarios are possible for INGOs: transform, die well, or die badly.

These changes allow for a level playing field in civil society in which people take part as equals, regardless of what organization they come from. This enables funders to learn from their grantee partners and to discuss issues such as unrestricted funding which civil society says is the most effective form of sustainable funding. A key instrument in this new way of working and doing development differently is the formulation of a ‘community of practice (CoPs)’, in which communities have an opportunity to learn together.

SP: These communities of practice are what we call “Experiential Learning Institutes”, where people can say, “this is what I have succeeded on, and this is what I haven’t.” And when something has not worked, they share that experience too to discourage others from repeating the same mistake. The more we can have these communities of practice, the more we create space for learning, relearning, and unlearning. As well as peer learning, the NGO Forum conducts training with partners, using an REI framework (Relevant-Empower-Innovative). The REI framework seeks to ensure that the trainings are relevant, delivered in an empowering way, and uses innovative techniques for knowledge and skills transfer.

Facilitators in the training don’t claim to know it all, but instead support a process to show that something is possible, and can be done, and the innovative element brings out an experimental factor to the trainings. This is helping to re-imagine how to do things differently, using philanthropy as a way to do this. As we engage in our work, we have turned communities into large laboratories where we run development experiments. We use an iterative and adaptation approach

An important result of the work so far is the connection between action at the national and sub-national levels. How are we sharing power? We are giving the regional partners space in the NGO Platform because these trainings are run by local actors. The feedback is good because people at both levels are talking to each other about things that matter. We are building relationships across the country and give priority to work in the regions.

BK: What about the government – how have they responded to your work?

MI: There’s a love-hate relationship with the government, where mixed messages seem to be the norm. Sometimes, you get a feeling that there are “two governments”. In private, they support our work, but in public, they say a different thing and can be quite critical. It feels like, on the government side, they love you but can’t come out in public to say that. We live with the mixed messages and tension – a careful dance. The dance builds on our collaborative model and makes sure that at all times we stay clear of being adversarial and using language which could be viewed as inflammatory and corrosive.

We are putting much effort into rebuilding the relationship with the government. This is critical to the future success of civil society in Uganda for many reasons, not least the importance of helping to shape new legislation encouraging more corporate giving with tax incentives. The NGO Forum has successfully inserted itself into an upcoming High-level meeting with government officials and donors on the sustainability of the SDGs and is even hosting a session during that meeting, while simultaneously running compliance clinics to help NGOs to meet the legislative and administrative requirements of the state. These compliance clinics are critical to building the sector’s substantive legitimacy (i.e. adherence to the organization’s DNA – its mission) on the one hand, and on the other procedural legitimacy (adherence to legislative and administrative requirements of the state).

In its plans, the NGO Forum wants to see a memorandum of understanding between civil society and the government to ensure that development in Uganda is conducted using a partnership model. Such MoU can be between the NGO Forum and the MDAs.

Conclusion

The cause for social justice and the fight against poverty and exclusion has gotten more urgent, yet the sails of shrinking space have seemingly gained more momentum than the wheels of civil liberties and rights. It behooves the leadership and membership of the Uganda National NGO Forum to exert themselves in terms of financial, human, and technological resources to mount a formidable pushback against shrinking political space.

The shrinking, shifting, and disruption of space for civic mobilization and action driven by governments and their transnational partners is likely to remain a challenge to advancing and achieving the NGO sector mission. This is because the forces that undermine civic and political work are unrelenting and re-inventing themselves as global and national pressures from social movements and climate disasters intensify.

However, the Ugandan story has much to teach us about how to turn a crisis of closing civil society space into an opportunity. The words of Sun Tzu in “The Art of War” ring true: “In the midst of chaos, there is also an opportunity.” As the NGO Forum stated in their 2021 annual report for the Giving for Change programme, they have embraced and taken on the moniker of this bold and transformative programme that leverages innovation and creativity.

Solutions to the problem of closing civil society space are hard to come by, so the Ugandan example deserves to be lifted as a potential route that others can follow, both within the Giving for Change programme and beyond. As we can see, the focus on domestic resource mobilization, equality, cooperation in civil society partnerships, and being driven by the needs and demands of local communities, all yield positive dividends. What has been achieved in a year and a half since the Giving for Change programme started in 2021 is remarkable.