By Barbara Nost and Tarisai Jangara

This blog post first appeared on the Alliance Magazine August 13, 2021.

Many of us representing local organisations in the Global South have experienced situations in which one is left speechless or outraged.

These are real-life situations that are purely hurtful where the Global South organisation encounters three hurtful behavioural patterns – superiority, arrogance and dominance. In these situations, one chooses to either exercise extreme humility or risk not having funding for their organisations. These scenarios might appear normal to some organisations especially in this environment where civil society might be competing for funding or where funding is on the decline.

There is a scenario in which the log frame for a new joint financing agreement is agreed with the group of donors as a result of joint meetings over a period of months. One donor steps out of line and requests for a bilateral meeting, during which they haggle over the agreed log frame format and the adequacy of the overall impact indicator, which according to the donor ought to be replaced. The Global South organisation refuses to make the amendments and as an expression of the donor’s disagreement with the final shape of the programme he concludes the meeting by saying ‘This programme is doomed to fail.’ The relationship ends right in that meeting.

The second scenario is when a new programme proposal is drafted following consultations with civil society, desk research and careful preparation over a period of various months. The donor requests for a meeting at the office of the Global South organisation chairs the meeting and imposes new activities. With the negotiations being too advanced and the financing agreement about to be signed, the Global South organisation agrees to include these activities, even though they think they add no value to the programme. As the programme is being implemented, the budget for these activities remains unutilised – and is re-assigned to finance other activities, as the implementation of the activity would contravene the demand-driven approach they so much advocated for in the first place.

The Global South organisation must be courageous enough to address hurtful donor behaviour and the donor must be willing to self-reflect on entrenched behaviour based on arrogance, superiority and dominance.

In the final scenario, the Global South representatives are flown to the Global North country by an international NGO to spend an entire week away from their offices providing inputs into the concept note and proposal which are prepared by the international NGO. After all the brainstorming and inputs, the INGO neither shares the final proposal and budget submitted nor the final outcome of the competitive call for proposal with the Global South organisations. In fact, the outcome of the call for proposal is communicated after Global South organisations request for an update. The INGO then makes a call for proposals and invites the same organisations that contributed to the formulation of the proposal to apply for a sub-grant. After all the effort they helped in designing the project, Global South organisations feel deflated, having given their time and knowledge of the local context.

Navigating ‘hurtful’ scenarios in the aid sector

Yes, funders must begin to see local NGOs as equal partners and they need to foster relationships that are based on mutual trust and respect. After all, local organizations bring crucial knowledge about the context they operate in, which helps to develop projects and programmes.

But how can civil society leaders in the Global South make changes in their behaviour to navigate such complexities? What needs to happen to enable local organisations to say ‘no’ or ‘question’ the unpleasant scenarios in the traditional aid sector? Development practitioners should not constantly fall into various roles and relationships in chase of available resources, giving in to donor demands. The much-needed change begins with the Global South self-introspecting, acknowledging and challenging the hurtful scenarios they encounter in their everyday work. Until then, any efforts towards sustainable development by national institutions will continue to be undermined unnecessarily.

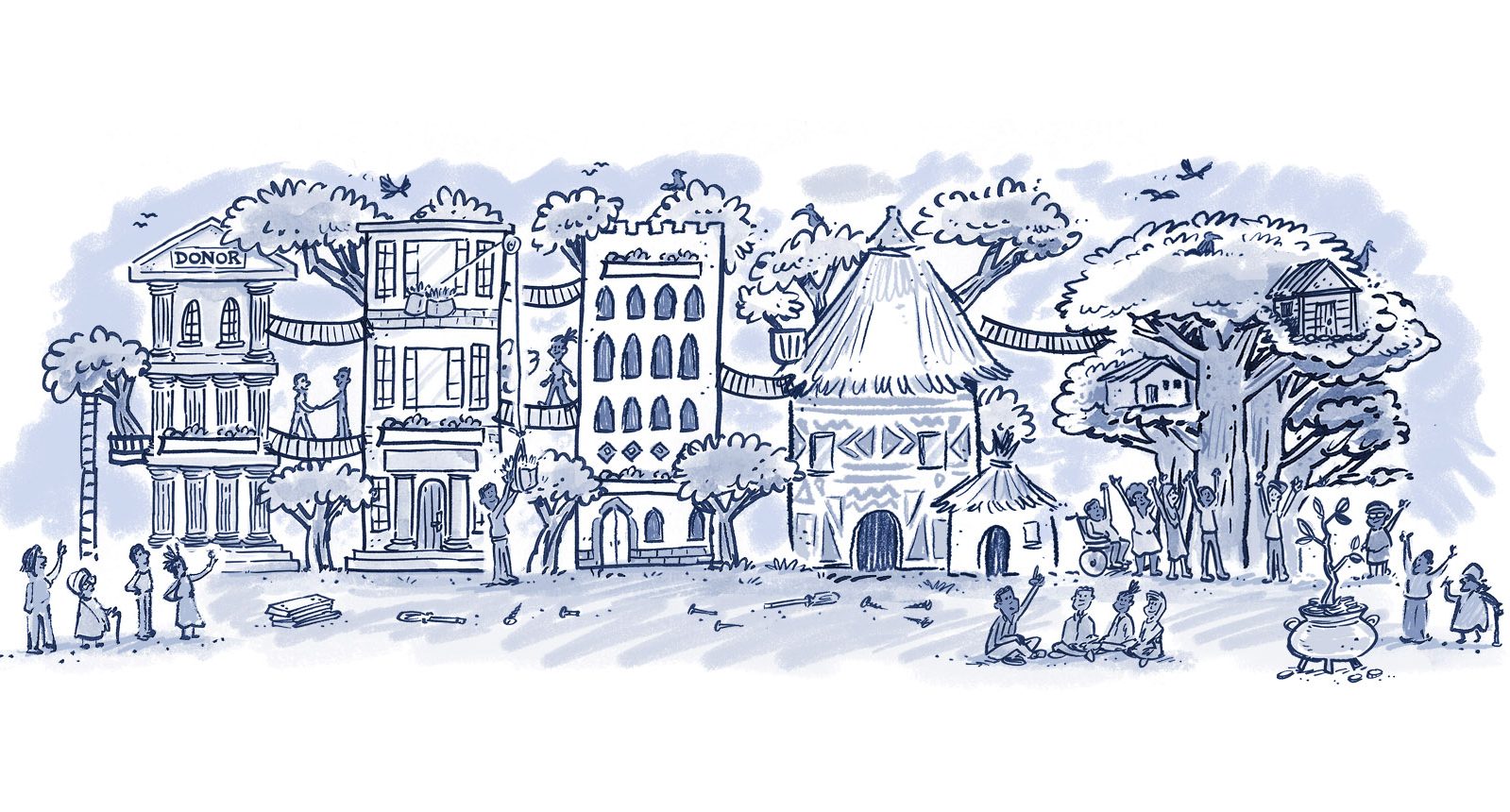

The research by Global Fund for Community Foundations (GFCF) commissioned by GlobalGiving ‘What does it mean to be community-led?’ captures the discussion around helpful and hurtful funder practices. Helpful practices, such as open communication, humility and respect, curiosity and willingness to learn and adapt creative solutions, patience and flexibility can prevent these scenarios depicted above to occur. Nonetheless, change has to happen on both sides. The Global South organisation must be courageous enough to address hurtful donor behaviour and the donor must be willing to self-reflect on entrenched behaviour based on arrogance, superiority and dominance. Only this will help decolonize aid in practice and above all, help produce results that are meaningful and impactful.