It may be surprising, but this is how development aid has functioned for about 75 years. Less than 10% of international aid funds directly flow from OECD’s DAC donor countries to CSOs of the Global South. Although additional funding might flow indirectly through INGOs or donor organizations to CSOs in the Global South, there is no doubt that a significant portion of these funds are used in the donor country itself. Such indirect funding often moves through multiple layers of organizations within the donor country. By the time it reaches the CSOs of the Global South, the real allocated funds have been extensively reduced.

Even after receiving aid, CSOs in the Global South encounter significant challenges in deciding how the money should be spent. Procurement of goods and services during the project implementation poses significant barriers, as donors usually require local CSOs to follow their guidelines while purchasing materials and resources using donor funds. This often requires them to use the aid money to buy materials and engage human resources from the donor country or a selected group of countries and their companies. The development aid term for all this is “Tied Aid,” a reference to restrictions on CSOs from the Global South to access and utilize funding and resources freely.

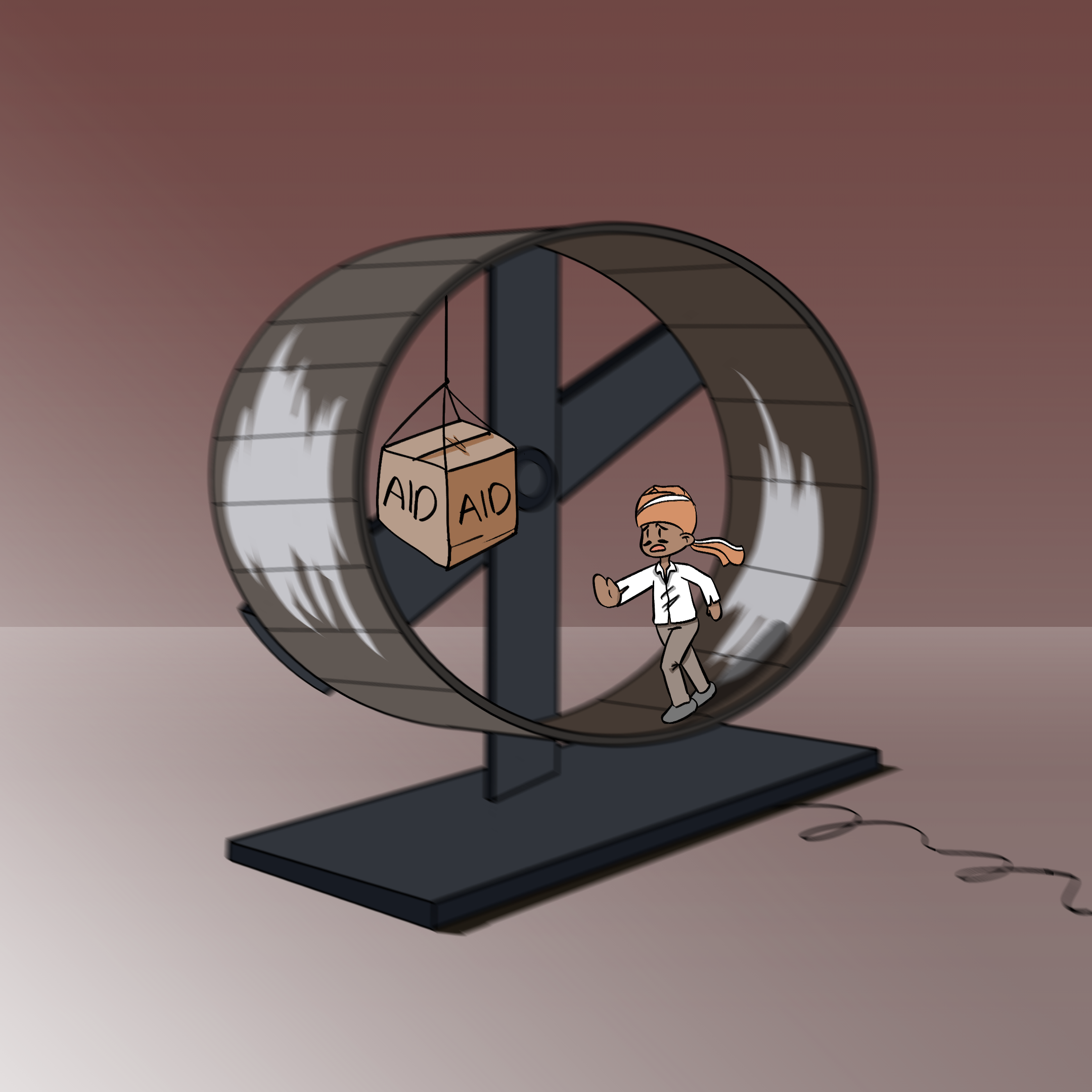

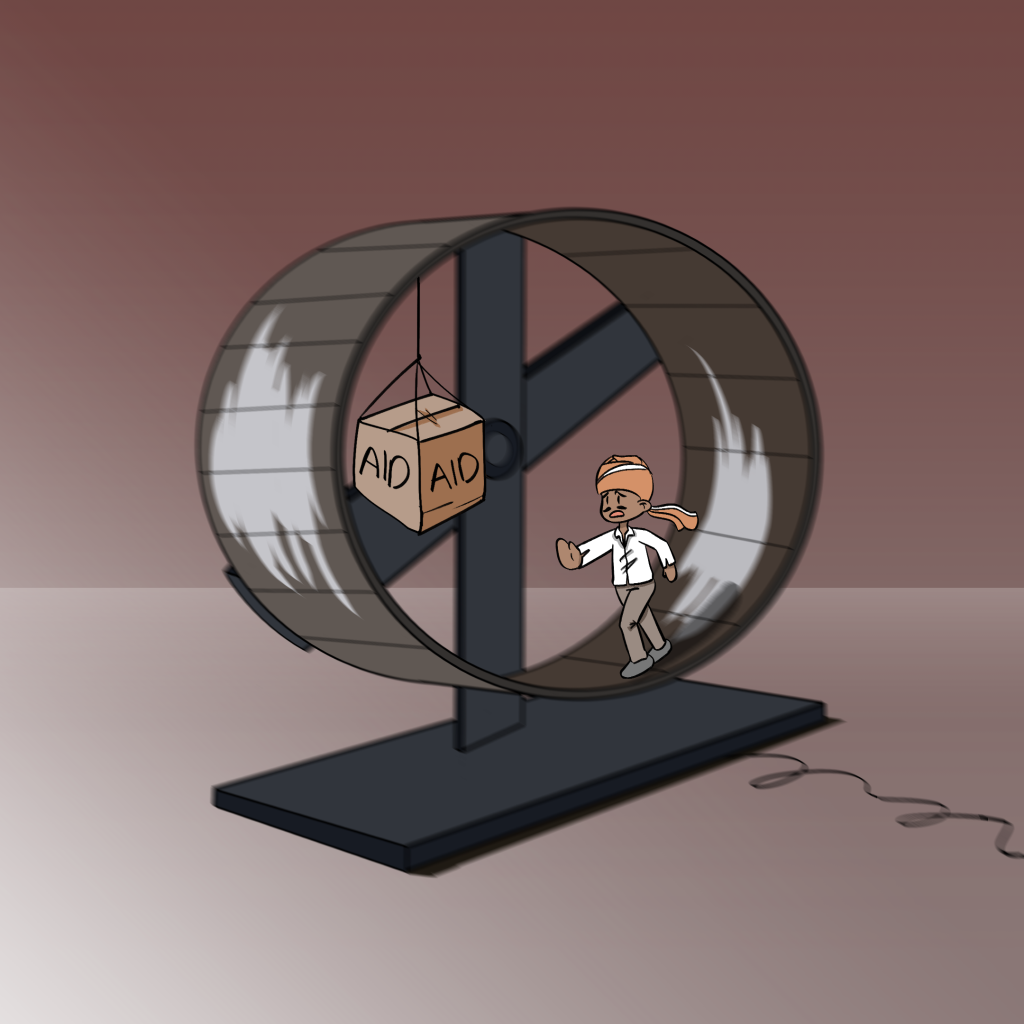

Tied aid not only hinders the ability of CSOs from the Global South to address the local community needs effectively and independently, but it also humiliates them, as it limits their autonomy and opportunities, and also undermines the products, capacity, and expertise of their community and their country. The micro-management of aid by the donor organizations and countries asserts their authority and control over the development process and global commitment to sustainable development. Its existence erodes and undermines the confidence of activist and grassroots development practitioners and reinforces the notion that they cannot manage their own affairs optimally. Tied Aid perpetuates a vicious cycle of underdevelopment and increases power imbalances between rich and poor countries because it directly or indirectly prioritizes donor countries’ interests over recipient communities’ needs. Ironically, because Tied Aid also restricts who can apply for grants, it also contradicts the principle of a free market economy, an ideological cornerstone of the Western world.

Tied aid not only hinders the ability of CSOs from the Global South to address the local community needs effectively and independently, but it also humiliates them.

For grassroots activists and organizations like ours, Tied Aid severely restricts our ability to compete for and implement grants compared to counterparts in donor countries. Restrictive policies and language barriers disqualify CSOs from the Global South from competing for funding on an equal footing. Simply because organizations exist in donor countries, they wield more power and control over resources than similar organizations based in the Global South. Their voices are given more weight in shaping the development narrative, overshadowing ours. Even local community activists with decades of experience are often overlooked in favor of newcomers from the West. Such dynamics undermine the concept of localization and prioritize the interests of donor countries and organizations.

It may be surprising, but this is how development aid has functioned for about 75 years. OECD DAC countries are well aware of this situation, yet they have not been able to make a significant change. DAC members have been coming together regularly for about two decades to take a significant step to untie aid. For example, in 2001, the OECD DAC came together and provided recommendations to remove legal and regulatory barriers to international competition in ODA procurement. Later, The Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness endorsed the recommendation made. Every year the committee holds review meetings, which has become a waste of time and energy, as they are unable to make a transformable shift in tied aid policies and practices.

At this time, when governments of developing nations are increasingly skeptical of foreign funding, barriers imposed by the donor countries put grassroots CSOs at enormous risk. As powerful elites in the Global South continue to discredit CSOs in the name of ‘foreign agents’, tied aid contributes to this narrative, muddying the waters for activists. Working in tied aid conditions raises doubts among grassroots changemakers about whether they are genuinely working for the betterment of their community or serving foreign agendas. For instance, in Nepal, the Social Welfare Council (SWC) has implemented a mandatory policy requiring approval for all foreign funding received in Nepal. The approval process, on the other hand, is burdensome, involving bureaucratic hurdles and size-based taxes for project approval.

Despite pledges to support marginalized and vulnerable individuals and communities, donors have often failed to fulfill their promises by holding power and resources. Decades of studies have shown that tied aid practices have worsened the situation of development action. The increasing distrust among donors and community activists is likely to not only affect the development spectrum but also the politics and world governance towards increasing populism and control of the authoritative regime. Therefore, it is most crucial for civil society actors from both the Global North and South to act collaboratively to untie aid.

There are several actions we can take as a global civil society to untie the aid systems along with pushing for the revision and reform of international and even national policies that benefit powerholders. For example, consciously advocating for policy change that promotes transparency, accountability, and grassroots participation in aid planning and management possesses huge potentiality to transform the traditional funding structure. Creative activism efforts to publicly criticize bad practices in the international aid system can also put pressure on donors and international organizations to review their funding modality. It can further help activists at the grassroots to raise awareness about the challenges and effects of tied aid and local efforts that are undermining civic freedom. However, collaborative efforts are vital in making a transformation in the aid system. There must be strong partnerships between international organizations and grassroots civil society so that they can collectively amplify voices to untie aid. Additionally, creating open and accessible transparent aid management systems at both an international and national level can help ensure that aid is flown, managed and used keeping communities and people in need.

Untying aid is not only limited to controlling aid resources by the Global South. It also means that communities, CSOs and activists at the Global South are recognized, respected and celebrated for their efforts and local expertise. Aid should be a means to innovate change in the local community along with promoting local knowledge. Therefore, significant funding should be allocated to ‘try and test’ new ideas for change. It may seem that overcoming challenges posed by tied aid is difficult, but if we unite – change is possible, maybe it takes some time, but change is inevitable.

Nishchhal Kharal is the Executive Director at Freedom Studio and is based in Nepal